Character Study: Ellen Ripley

Dan O’Bannon’s lean, mean script for Alien (1979) might just be the greatest screenplay ever. There’s no point in qualifying that. I’ll just let you simmer.

I

The screenplay is sparse, almost poetic in its simplicity. There is so much white on the page that it seems nearly impossible that such a richly complex film could have sprung from this DNA.

There are volumes that could be written about the world-building, the set design, Sigourney Weaver’s star-making turn as the lead Ellen Ripley, and the pitch-perfect cast of character actors backing her up.

It has recently been brought to my attention that “sequels” to this movie exist. I refuse to believe this hogwash, as there can only be one Alien.

Let’s focus, however, on the screenplay, and particularly the character of Ellen Ripley.

II

Alien is many things, but above all, it is a horror movie. Its classic pitch was “Jaws in space,” but it’s so much leaner, so much meaner than that. Scrubbed of all the politicking and the male bonding crap.

I prefer to think of it as The Texas Chainsaw Massacre in space, with the paranoid grace note that the Company might just have sold you to Leatherface’s family for a profit.

And yet, no one really remembers the person who survives the horror movie. It’s just the chaste girl, the one who doesn’t talk too much or get down with her boyfriend in the back of the van before anyone even mentions head cheese.

How is it, then, that we take Ellen Ripley, a character with zero backstory, and turn her into a household name? In fact, a one-name household name--Ripley--like Cher or 90s pop-folk darling Jewel.

Ripley is synonymous with feminine empowerment: logos, pathos, self-sufficiency, care, and grit in a package that simply oozes class.

One might argue that it’s in the actor: how much of that is simply Sigourney Weaver? No one ever asks, it seems, how much of Ripley did Sigourney Weaver take on.

III

Let’s analyze Ripley’s position on the ship. She is the Nostromo’s Warrant Officer. A Warrant Officer--and yes, I looked this up--is essentially an officer charged overseeing care, maintenance, and operations of the ship.

The Warrant Officer essentially has a commission separate from the officers and the enlisted; on the ship, the Warrant Officer acts as the go-between, negotiating between the commanders and the commanded.

Historically, Warrant Officers oversaw stores on the ship and kept its logs. Literacy was a requirement when this was a skill rarer even than it is today. Some Warrant Officers would even stay with the ship when it was out of commission, such as in the dock for repairs.

This might seem simply to be a useless bit of trivia, but it is not; in fact, it gets straight to the point of the film: it is Ripley’s actual, stated job to protect the Nostromo and its crew. Notice how she keeps the ship’s logs.

In any well-written script, of course, you take a person who has a specific talent, skill, or obligation, and then put that person in the position that tests that specific in its most extreme case.

In our case, of course, we get Ripley’s obligation from her job description. Before we even meet her--by virtue of her position--she is tasked with protecting the Nostromo, whatever shit might be about to go down.

IV

Let’s go back to the plot for a moment.

When the landing team is out of communication, Ripley discovers that the message is a warning. She cannot, of course, reach the team to get them back on the ship.

However, when the team comes back, Ripley is the commanding officer on board the ship. She steadfastly refuses to let the crew back on board without following quarantine procedures. However, she is prevented from achieving this by Ash, who, against protocol, lets the landing team back on to the Nostromo.

Fast forward through the fun and games until the Alien is loose and has captured Dallas. Ripley is now the Commanding Officer, and when Lambert suggests escaping in the shuttle, Ripley shuts her down: the ship must be protected.

It is only when Ripley learns from Mother, the ship’s computer, the true nature of their mission, that her allegiance falters: the Company wanted to collect a specimen of the Alien, ostensibly for its research into a super-weapon. More disturbingly, Ash was in on the joke.

No fool, Ripley will not accept her loyalty being met with betrayal. She decides to leave with Parker and Lambert in the shuttle, destroying the Alien by initiating the self-destruct sequence on the Nostromo.

After Parker and Lambert are killed, Ripley tries to stop the self-destruct sequence: one last attempt to protect the Nostromo from her (the ship’s) cruel fate.

Unable to override the self-destruct, Ripley is forced to abandon the ship and get on the shuttle. At this point, Ripley is stripped of everything in her identity (and, not unintentionally I presume, the vast majority of her clothing): the ship, the rules, the crew, faith in her Company. She and the Alien are engaged in a primal, no-distraction fight for survival.

V

Ripley’s special skill is also her major fault: abiding by the rules.

The flipside of this record is that she knows damn well when the rules are bullshit, and in such a case she has no hesitation to break them.

This creates the great philosophical conundrum of the film: if she had followed the rules, the landing team never would have been allowed back on to the Nostromo.

Yet… Ripley soon enough learns that the rules are set by the Company that we learn to be corrupt. She and the rest of the crew are pawns in a game they didn’t even know existed.

Is there honor, glory, or comfort in following the dictates of a corrupt overlord? Perhaps for a while, if you assume immunity for yourself.

Historically, however, this is foolish: there is no telling when these dictates will turn directly against you.

Ripley speaks to the hero in all of us as she embodies Niebuhr’s Serenity Prayer:

Father, give me the courage to change what must be altered, serenity to accept what can’t be helped, and the insight to know one from the other.

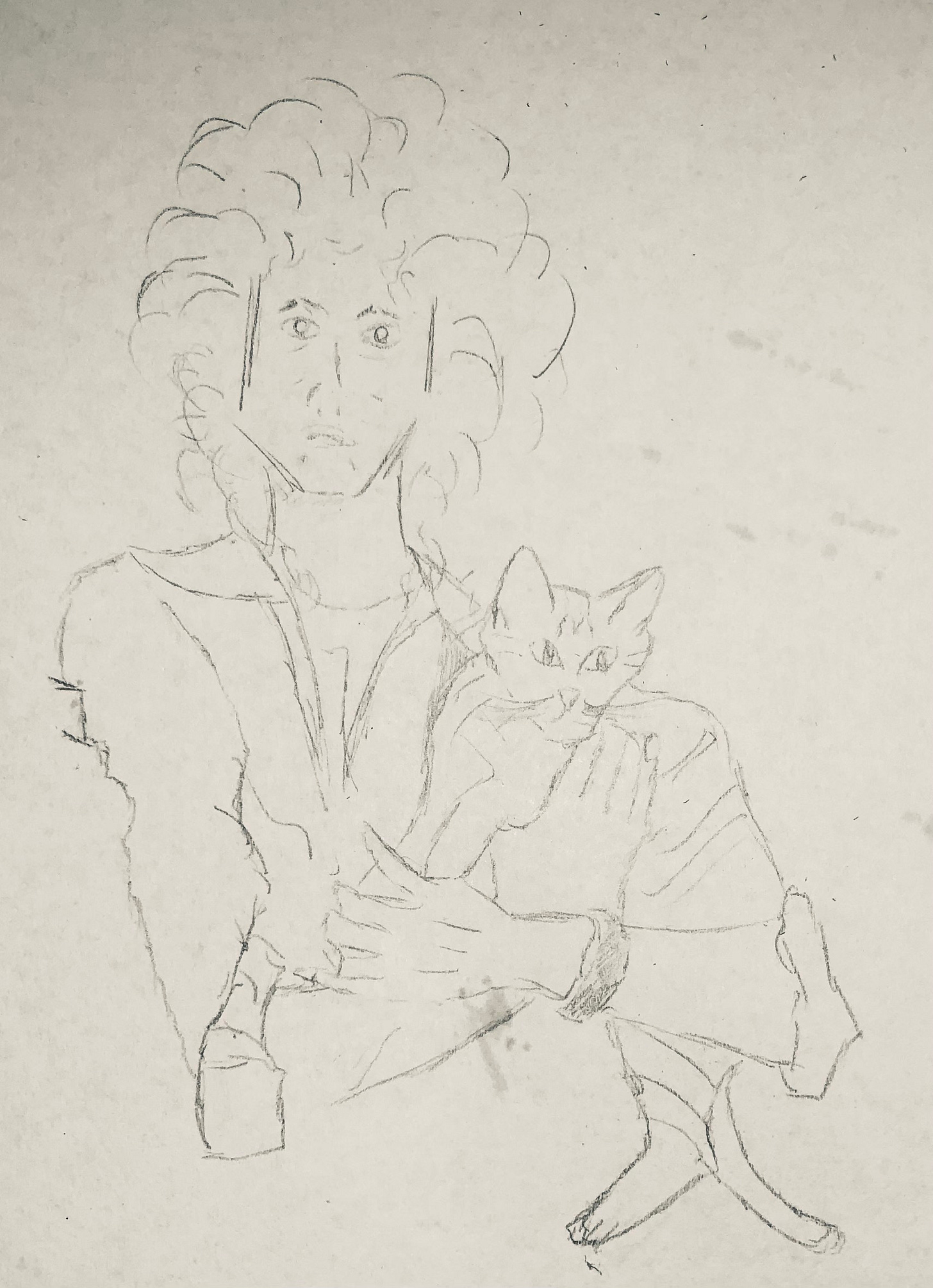

Ripley knows the difference: she knows when not to let people on the ship, she knows when she’s being taken advantage of and always works toward the best outcome for her ship, her crew, Jones the cat, and last of all herself.

The clarity, presence of mind, grit, and strength of Warrant Officer Ellen Ripley is what makes her Ripley.

VI

Contextual aside:

Nostromo (1904), by Joseph Conrad, tells the story of Nostromo, an Italian immigrant in a South American colony (effectively Colombia) who is widely respected throughout different classes in his town of Sulaco.

Nostromo is Italian for “boatswain,” a synonym, of course, for Warrant Officer.

The wealthy European mining interests realize Nostromo’s sway among the town’s lower classes, and he is tasked with smuggling valuable silver out of the town to keep it out of the hands of revolutionaries. After succeeding at this, he plays a pivotal role at defeating the revolutionaries and keeping the Europeans in power.

Nostromo himself is thought incorruptible. However respected he is among the different classes, never leads to a true entrée among the upper class. He becomes obsessed with recovering the silver that he has hid, and these exploits yet again put his very life in danger.

This is a cautionary tale, but cautionary of what? Let Ripley answer the question, succeeding where Nostromo could not.

VII

In screenwriting, the perfect character embodies the things that we are unable to embody in our day-to-day lives, who engages with the experiences that we archetypally long for.

This is why we don’t need to know about who stole little Ellen Ripley’s stuffed panda bear in kindergarten. It’s not helpful; any psychological read on her that we gain from this is cloying, artificial.

Rather, we learn about Ripley from the position that she has chosen to take on the ship. We learn about her from the actions that she takes: this is a thoughtful person who takes her job seriously. We learn from the bullshit that she refuses to take: this is a woman not to be trifled with. We learn from the fact she literally, not figuratively, saves the cat.

Fundamentally, Ripley acts as a perfect audience proxy in the film. By no means a passive observer, she exhibits a sort of common sense that we can recognize as correct the moment we see it. Ripley does what we wish that we could do: she survives an impossible situation, refusing to compromise her principles.

We want to kick the bully in the balls, yet we don’t.

We want to tell the boss to go fuck herself, yet we don’t.

We want to confront the power structure and believe that we can successfully bear the consequences, yet we don’t.

Ripley tries her hardest to play by the rules as long as she believes that the rules are worthwhile; indeed, some of them are: cf. don’t let a compromised landing party back on the ship without quarantine.

As soon as she realizes that the power structure itself is corrupt, she changes her tune immediately and is concerned with the well-being of her crew, then her ship. If she can save the ship, great, but fuck the company.

She’s willing to deal with the consequences but we don’t yet know what these are. We do know that she has saved herself, and that in this true life-or-death struggle, she has prevailed.

We are all sold the fiction that rules exist for the common good; when we grow the fuck up and learn that rules exist primarily to benefit some arbitrary power structure, it is downright crazy-making. We have all been sold a lie, and that has never been more apparent than it is now.

Nevertheless, our reactions tend to range from silent complicity to pissing and moaning on social media to thoughtless, chaotic public acts of defiance. None of these seem to be reliable, effective, or even constructive methods of comporting oneself.

Considering Ripley is a good place to start: allow the perspective to shift as new shit comes to light. Be a concerned citizen: protect the crew, even Jones. Do what you can for your charge, the ship. As soon as those boxes are checked to the best of your ability, blow the fucking monster out the airlock.

She is us in more ways than we would like to admit: she is a hero for a society that is waking up to the bad deal it has been unwittingly sold. Ripley encourages us to remember this: the Company doesn’t need you; you were expendable in the first place.

VIII

The takeaway: you don’t need a convoluted, tearjerking backstory that you’ll only learn through cack-handed exposition; you need a character who fits--on the level of skills, attitude, demeanor, personality--into her story.